The Doomed Boom: Education and Seattle's Stall

Washington State managed to produce a 40-year tech boom with a mediocre education ecosystem. Is the end in sight?

Tell the story of the successful tech boomtowns of the past four decades and you’ll find research universities inextricably woven in. The story of Silicon Valley can’t be told without Stanford. The “Massachusetts Miracle” of Boston and the suburbs around Route 128? Deeply connected to MIT, Harvard, and the plethora of other research universities in the region. And without Duke, UNC-Chapel Hill, and NC State the “Research Triangle” wouldn’t be anything more than another swath of Carolina piedmont.

Seattle’s boom, beginning with the arrival of Microsoft in 1979, has a different origin story. Sure we have a world-class research university here, Bill Gates and Paul Allen famously used its computing infrastructure as high school studentns nearby, but its presence is almost accidental. Gates and Allen followed one another to Harvard, and then to Albuquerque. Their move back to Seattle was not necessarily because that’s where the talent was, but it was where the talent could be recruited to relocate to.

The boom would shift into a higher gear fifteen years later with the founding of amazon.com in a suburban garage. Jeff Bezos had been raised nowhere near the Pacific Northwest and drove across the country to found the company. In deciding where to base an online mail-order retailer that could, in theory, be based anywhere it wasn’t proximity to great universities or the talent they produced that drove the decision. In a 1996 interview, Bezos admitted that Silicon Valley was the place to be for talent. California posed a challenge to the amazon business strategy, however. At a time where mail-order retailers were required to collect sales taxes only in states where they had a physical presence, Bezos angled for a smaller state so that a higher percentage of customers could enjoy a lower price by evading taxes.

Tech boomed in Seattle despite the relative shortage of locally-trained professionals. Entrepreneurs overcame this disadvantage by recruiting talent to the region. Recent American Community Survey data show that Washington is exceptionally reliant on college-educated workers born out of state, trailing only Colorado and the District of Columbia.

Washington needs to import highly educated talent because it’s not a state with the infrastructure to produce much of its own. Massachusetts, home to thriving knowledge industries, has 11 “R1” research-intensive universities in a state of 7.1 million people. California, which like other western states developed later and lacks the dense network of private colleges found further east, has 14 “R1” institutions serving 40 million people.

These statistics give you a sense of the norm across the larger United States. Generally speaking you can expect to see one research-intensive university for every two-or-so-million people. Massachusetts, a higher-education dense environment, has one for every 600,000. California, the highest-population state, is near the other end of the spectrum with an “R1” institution for every 2.86 million residents. New Jersey is a bit lower, with a ratio of one institution per 3.1 million residents. Among the 21 most populous states, all but one have a ratio somewhere in the range between Massachusetts and New Jersey.

The exception is Washington, with just 2 “R1” institutions serving 8 million people. Tennessee, a slightly smaller state by population, has twice as many research-intensive universities. To find a state with a more sparse higher education ecosystem, you’ve got to go to number 22 on the population list, Minnesota, where there is just one institution serving 5.8 million people. And needless to say Minnesota has not enjoyed the sort of tech-driven population boom the Evergreen State witnessed. The two states were the same size in 1980; Washington now counts about 38% more residents.

If only the lack of major research universities were the true extent of Washington’s education problem.

What’s the matter with Washington’s education system?

When you get right down to it, the answer is money. Washington has subsisted for years on a “red state” no-income-tax revenue model that manages to barely provide adequate services because the state is relatively wealthy. The state’s status as a relative tax haven may be one reason why companies like amazon have found it easy to recruit highly-paid workers here. One could think of Washington State of the Microsoft-amazon boom years as the very model of trickle-down economics.

To establish that yes indeed Washington has a less-than-stellar public education system let’s just look at a few outcomes. In Federally-administered standardized tests, just 31% of 8th graders met the standard for proficiency in reading — only 30% in mathematics. In a state that ranks among the top 10 in terms of income, these results rank as indistinguishable from the (quite mediocre) national average.

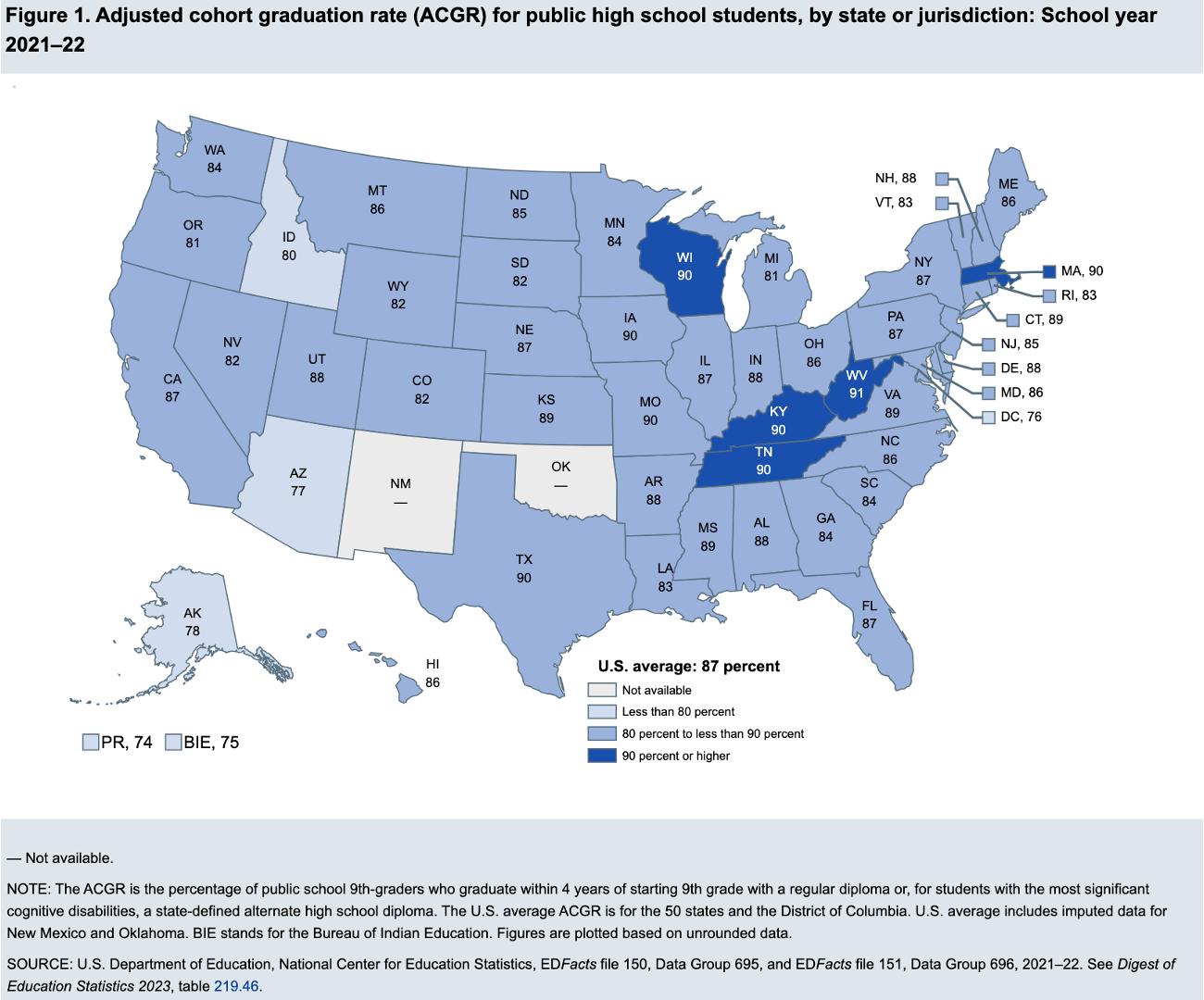

The middle-school test performance of our economically advantaged student body may disappoint, but things only get worse as our students age. In the most recent cohort studied, Washington students posted a high school graduation rate three points below the national average.

The news gets worse still. Even if they graduate from high school, Washington students show remarkably little interest in continuing on to higher education. Among the 50 states plus the District of Columbia, Washington ranks 40th in terms of FAFSA-completion rates.

In recent years Washington’s high school graduates have had only a 50/50 chance of enrolling in any postsecondary institution the next year, more than 10 points below the national average.

This is all bad, right? It gets even worse. Even if they make it to postsecondary, which is a relative long shot given our lower-than-average HS graduation rates and lower-than-average direct enrollment rates, Washington’s students perform worse than the national average in terms of actually completing a degree program. This is a new development over the past few years; the college of entrants of 2012 kept pace with their national peers. The most recent cohort falls 5.5 points below the national average, and 15 points below the completion rate in Massachusetts.

So if you came into this newsletter thinking that Washington was doing ok, hopefully you are completely flabbergasted by now. You should be. How is it possible that a state with a tech-driven high-income economy can be doing this incredibly badly at educating its students?

Any time you have a systemic failure like this it’s hard to pin things down on any one cause, but it should be stated that Washington is by no means spending lavishly on its education system. In a state with a cost of living among the highest in the nation, we’re nowhere near the highest in terms of per-pupil funding in our K-12 system.

And particularly given our state’s wealth, we aren’t investing a lot of public dollars in our higher education system either. Now, to be clear, money is certainly not the only determinant of education success. It’s not as though New Mexico’s higher education system is the envy of the world. But clearly California well outpaces Washington. Massachusetts doesn’t, necessarily, but the Bay State has a rich network of private higher education institutions that the Evergreen State just doesn’t.

We don’t spend very much because, in the grand scheme of things, we don’t tax very much. In a recent analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Washington ranked 48th in terms of the net state and local tax rate, ahead of only Alask, Wyoming, and South Dakota. None of those being states that have ever enjoyed any kind of tech boom.

Whither the boom?

Most economic booms are a product of happenstance. A region happens to be sitting on top of a natural resource that is highly valued at the time. An inventor makes a discovery in one place that could have been made any place. The forty year boom in Washington state was driven by entrepreneurs with idiosyncratic reasons for wanting to be here, who realized that the region’s natural amenities would help them globally source a workforce. One of these amenities, assuredly, was the state’s wealth-friendly tax regime.

The problem with recruiting people to a region based on amenities is that eventually the amenities get counteracted by disamenities. People move to an area with a reputation for a good quality of life and things start to change. The housing gets more expensive. The traffic gets worse. The quick and easy access to mountains and water becomes tangled in a web of suburban sprawl. In recent years, the Seattle region has been a net loser of domestic population, with sustained growth possible only because of immigration and an excess of births over deaths. The birth rate is declining all over the world. Immigration will decline with it, regardless of whether an isolationist regime continues to control national policy.

Some time ago Ed Glaeser wrote a history of Boston that emphasized the city’s ability to reinvent itself, from port town to industrial city to post-industrial tech hub. The key, in Glaeser’s argument, was education. A strong education infrastructure allowed the city to reinvent itself, to come up with something new to do when it was no longer profitable to continue with its existing industries.

Boom towns that lack this education infrastructure are at risk of becoming ghost towns. When the boom is over, people move away. Some years after Glaeser profiled Boston I wrote a history of New Orleans, describing how a lack of education infrastructure allowed the winds of economic change to pass the city by. A port town it once was, but it never significantly industrialized, and never became a tech hub. Today it exists in no small part as a tourist attraction.

Clearly Seattle is in no imminent danger of becoming a ghost town. But without an adequate educational infrastructure the city continues to be dependent on happenstance. The city waits, 30 years after the arrival of its most recent multi-billionaire-to-be, for another outsider to gift it a growth industry. It waits, with a system of tax revenue that depends critically on population growth. This growth is already subsiding, government already threatening to make cuts to the sector that offers the best hope of making the boom sustainable.

The Evergreen State sits at a crossroads.