Seattle's Capital Gains Tax Proposal and City Limits

Why a "hyperprogressive" tax might be a worse idea for 84 square miles of land.

On Tuesday, November 19th, Seattle’s City Council deadlocked on the question of whether to implement a capital gains tax. The proposal on the table would have mirrored the Washington State version upheld by voters this year. In Washington, the first $262,000 in capital gains per calendar year are tax-free. Beyond that, the gains are taxed at the rate of 7%.

Seattle’s proposal would have used the same exemption level, and taxed gains above that amount at the rate of 2%. A modest little tax, really. Estimates suggested that only about 800 residents would pay it each year, in a city of over 750,000. We often refer to taxes that hit the wealthy at higher rates as progressive. That is maybe too mild a term for a tax paid by only the top 0.1% of the population. Let’s say that this tax proposal would be hyperprogressive.

The hyperprogressive tax would ask a few hundred of the city’s wealthiest residents to pay an average of between $20,000 and $60,000 per year, according to estimates, for the privilege of maintaining a domicile in the city. On top of what they might already be paying in property taxes, sales taxes, and so forth.

What’s wrong with a hyperprogressive tax? Why not stick it to the top 0.1% (while letting the other 9/10 of the top 1%, not to mention everybody else, completely off the hook)? There’s just one problem, really. It’s that this tax would be too easy not to pay.

This is a concern with the state capital gains tax as well, and might help explain why the state’s capital gains tax collections dropped 45% from the first to second year of its existence.

There are two easy tax avoidance strategies. First, if you’ve got a million bucks worth of gains to cash in, instead of doing it all at once just space it out over four years and you get an extra return on your investment.

This is maybe a less viable strategy if you’ve got a billion dollars to cash in. That would take four thousand years to space out, and who can wait that long. This is when you lean back on tax avoidance strategy #2, which is just to skip town. You might laugh and say “who would abandon their Seattle abode just to save $20,000,000 in taxes?” (See Bezos, Jeff).

The bigger the taxing jurisdiction, the greater the sacrifice involved in tax avoidance strategy number 2. When we’re talking about a state-level tax, the mogul you’re trying to hit with your hyperprogressive tax needs to move their domicile to one of their out-of-state homes. But the City of Seattle? That little 84-square-mile postage stamp squeezed between Puget Sound and Lake Washington? A mogul need only sail their yacht to the other side of either body of water and their capital gains are safely out of harm’s way.

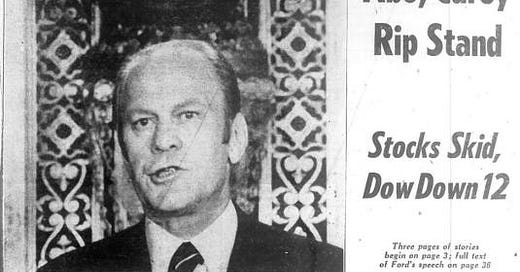

Half a century ago, New York City found itself in the midst of a fiscal crisis. This was the event precipitating the infamous headline in the New York Daily News, conveying the Federal reaction to Gotham’s request for a fiscal bailout:

Why am I bringing this up now? Bear with me. In the aftermath of the NYC fiscal crisis a series of books popped up to explain what happened. One of the more influential of them was Paul Peterson’s 1981 City Limits.

In Peterson’s telling, New York traveled the road to fiscal perdition because it had attempted to operate a municipal welfare state, using progressive taxation to take from the rich and operating a variety of programs to benefit the poor. (Which is kind of what Seattle is trying to do these days).

Peterson made a simple argument against this approach to municipal governance. When a small jurisdiction with porous borders taxes the rich to fund benefits for the poor, the rich move out and the poor move in. Which results in escalating demand for services alongside dwindling capacity to fund them.

One could quibble with Peterson’s argument, even more so with the evidence he marshaled to support it. There was a lot of other stuff going on in New York in the 1970s. Among other things, a city historically populated by immigrants who tended to move out as they moved up economically suffered the long effects of immigration restrictions between the 1920s and the 1960s. The turnaround in the City’s fortunes coincided with the resurgence of immigration.

But the cautionary tale here seems particularly germane to the question of hyperprogressive taxation. Tax a city’s richest 800 people a lot and you’re giving them an awfully good reason to leave. But what if you instead taxed the city’s 80,000 richest people, at one-hundredth the rate? To join the city’s top 80,000 earning households you’ve got to clear more than $200,000 per year, according to the Census Bureau. A forty thousand dollar price tag for living in the city is hard to ignore. A four hundred dollar price tag, even if paid by 100 times as many people, just over a dollar a day? Much easier.

So why doesn’t Seattle scale back the progressive taxation ambitions? Instead of soaking the very rich a lot, soak the merely affluent a little. It’s still progressive! Just not so progressive as to result in earning no revenue because the tiny number of people you’re trying to soak have easy ways to evade you.

Cathy Moore says the 2% tax would generate $16-51 M in the first year, which seems like a big range (https://www.kuow.org/stories/seattle-could-get-its-own-baby-capital-gains-tax). For a tax of this type, is it good practice to let it go to the general fund or specific causes, to promote good things / stop bad things? The intention seems to plug holes in the budget, but the upper end of $51 M seems like it could be used for a modest impact (that’s like $69 per Seattleite per year). Going from the top 0.1% income to about the top 10% (from 800 to 80,000) also seems to make the tax less avoidable without having adverse effects on the top 10%’s material conditions. What are the arguments city council members would make against the “tax more people but 1 hundredth of the rate” version?