Heidi Groover wrote an article for the Seattle Times today regarding the case of an International District landlord suing the city claiming that various tenant protections passed into law in recent years have rendered their apartment building worthless. As an economist who has written on housing affordability, I looked at this article the way an emergency room physician might review the vital statistics of a patient just wheeled in on a gurney.

There were two little statements that caught my eye. The first was a statement from a tenant advocate claiming that the city’s protections, which include among other things a moratorium on evictions in winter and a requirement to cover a tenant’s first three months of rent in a new apartment if they vacate yours after you raise the rent, are necessary to address homelessness which is worse than it has ever been.

This is akin to the ER doc hearing from a patient’s companion, “we keep giving her Tylenol, and her temperature’s higher than it’s ever been.”

The second statement came from the landlord filing the suit, noting that in the allegedly now-worthless apartment building the vacancy rate nears 45%. This is a cause for alarm bells. In a hot real estate market such as Seattle’s, why would apartments be vacant? This is akin to an ER doc discovering that a patient’s organs have begun to shut down.

Seattle’s tenant protections were enacted to make life a little better for lower-income families who face economic precarity. But given the symptoms observed here — worsening homelessness, landlords letting units lie fallow — it’s worth asking whether the cure might be worse than the disease.

Seven things Seattle asks landlords to do… and the one thing they can’t

Suppose you own a habitable dwelling in the City of Seattle. It doesn’t have to be an apartment building. There are tens of thousands of traditional single-family detached homes rented out by their owners inside the city limits. Here’s a subset of the things City ordinances expect of you:

If you rent to a family with school-aged children, or a schoolteacher, you cannot evict a tenant for non-payment of rent during the school year.

Since 2017, when your unit is vacant you must rent it to the first qualified applicant, on the (as far as I know unproven) theory that this reduces discrimination.

Since 2018, you are not allowed to rule out prospective tenants on the basis of a criminal history.

Since 2020, you cannot evict any tenant for non-payment of rent between December 1 and March 1.

Since 2021, you must provide tenants six months’ advance notice if you intend to raise the rent.

Since 2022, if you raise the rent by 10% or more, and a tenant chooses to move out, and that tenant earns less than 80% of median income, you are responsible for covering their first three months’ rent once they relocate.

Since 2023, you can’t charge a late fee greater than $10. With average rent for a one-bedroom nearing $2,000, that’s a cap of less than 1%.

The one thing Seattle can’t force you to do, if you own a habitable dwelling inside the city limits, is actually rent it out. If you own a single-family detached dwelling, you can always just sell it. If you own a multi-unit building, you can convert it to condominiums (although as you might expect there are tenant protections built into that process too). Or, worst case scenario, you can just not rent it at all. If you own a property, meaning you pay taxes and insurance on it, failure to rent means you’re losing money on it. But if you rent it out, you might lose even more money if your tenant proves unreliable in paying the rent and causes even normal wear and tear to the unit.

Seattle is losing rental units by the tens of thousands

Look around the Emerald City today and you’ll see construction cranes dotting the landscape. So it has been for the past decade or more. The figure below shows growth in the number of housing units inside the city limits, as recorded annually by the American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS bases its findings on a sample, so some of the year-to-year fluctuations in the chart may just be statistical noise. But by and large, the number of housing units in Seattle has increased steadily. Between 2005 and 2019, the city added over 185,000 housing units, two-thirds of those rental units. In this time period, the city transitioned from a majority-owner-occupied housing stock to evenly split between owned and rented units.

Something different has been going on in the most recent data. The number of rental units dropped even as the number of owner-occupied units continued to increase. In raw numbers, Seattle lost an estimated 24,000 rental units after 2019. Had the city remained on the same trend line it exhibited from 2008, the year of the global financial crisis, to 2019 we would have expected growth rather than decline. The number of “missing” rental units in Seattle, the number we see compared to the number we might have expected to see had we made a forecast before the pandemic, sits around 68,000.

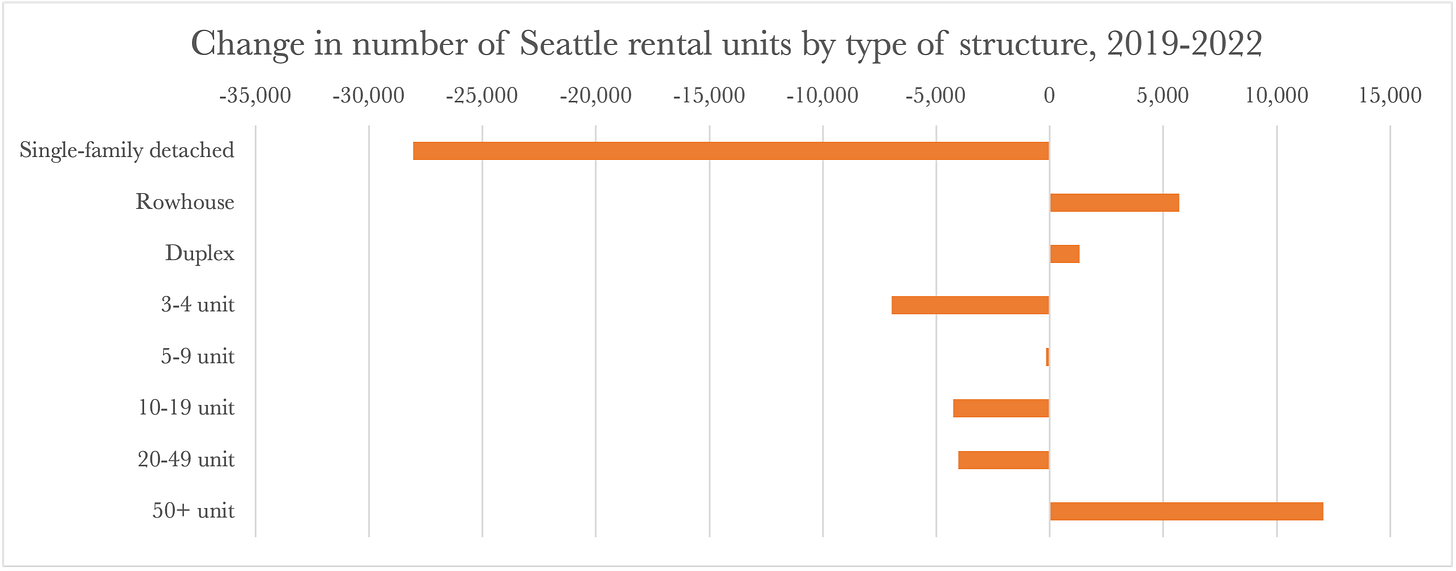

What’s going on? The next chart shows that one type of rental — a traditional single-family detached house — accounts for the majority of the rental unit decline between 2019 and 2022. We often think of apartment buildings when we think of rental housing, but single-family homes accounted for nearly one in four Seattle rentals as of 2019.

The owner of a single-family rental unit has a fairly straightforward path to getting out of the landlord business: sell. The decision to rent or sell a home you are not currently living in really comes down to expected financial returns. Sell and you cash out now. Rent and if things go well you’ll have a steady stream of income going forward. If things don’t go well… the more protected your tenants are, the greater the losses you might face.

Seattle has seen growth in the number of rented townhomes and rented units in 2-unit structures (which we’d traditionally call a duplex but could include accessory dwelling units in the same structure as a main dwelling). There has also been a lot of growth in large apartment buildings, of the sort one needs a crane to construct. But the losses, in total, have exceeded the gains.

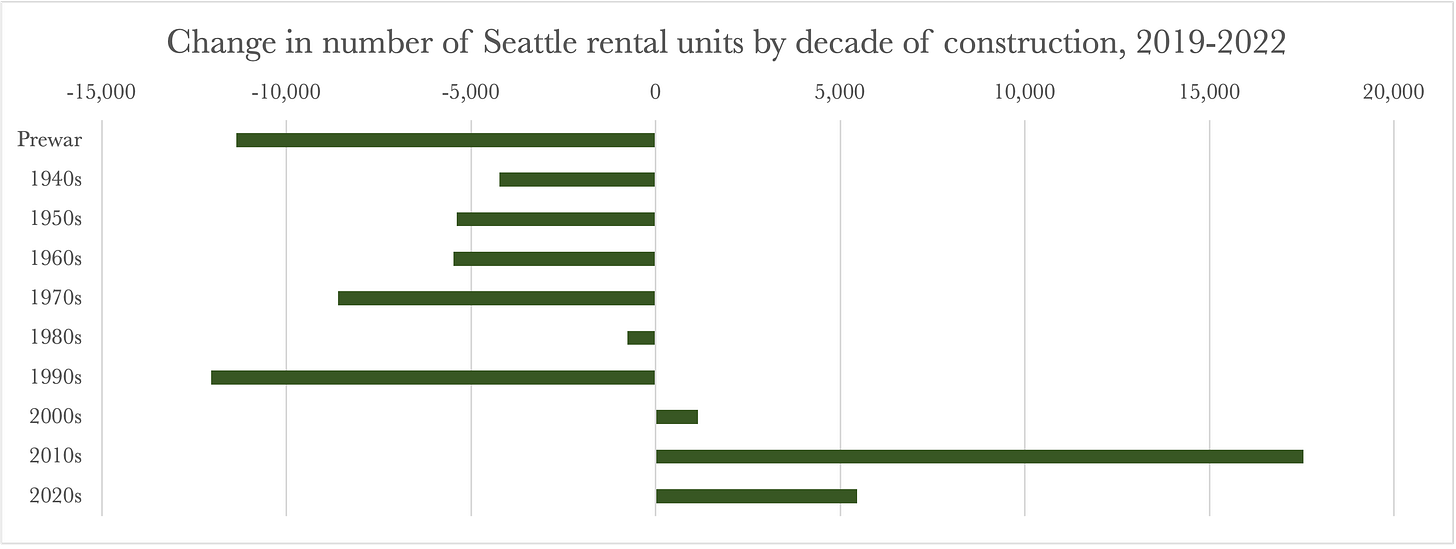

Perhaps most concerning from a housing affordability perspective, Seattle is losing older rental units swiftly. Between 2019 and 2022, more than 10,000 pre-World War II rental units were taken off the market in the City, either because they were demolished to make way for something new, converted to condos, or otherwise repurposed. The city did manage to construct thousands of new rentals in this three-year span, but those gains were more than offset by the losses in pre-2000 rentals.

So what do we do?

The City of Seattle operates what we might call a “privatized welfare state.” In a true welfare state, tax revenue would fund basic income support programs and subsidies for necessities such as food and housing. Seattle doesn’t collect anywhere near enough tax revenue to fund that sort of system, and if it tried it might find that more heavily taxed residents would just move outside the city limits. So instead the City has aimed to support worker incomes by requiring businesses to pay higher wages. It has aimed to support tenants who have lost a job or otherwise experienced economic difficulty by requiring landlords to keep them housed without rent payments for, in some cases, many months.

Seattle could, in theory, protect tenants using public (a.k.a. taxpayer) resources rather than landlord resources. Tenants displaced by rent increases could apply for assistance funded by the city rather than their former landlord. Temporary rent increase assistance could take the place of the required 6-month advance notice.

The problem is that these alternative solutions require public dollars, of which Seattle currently has a very significant shortfall. It would take a significant tax increase to fund benefits of this sort.

Some Seattle regulations impose burdens on landlords without much if any benefit for tenants. The first-in-time regulation is a classic re-arrangement of deck chairs on the Titanic. It mandates that this applicant, rather than that one, is entitled to the unit but does nothing to improve affordability or protect tenants.

Other Seattle regulations protect one class of prospective tenants at the expense of others. Forbidding landlords from considering criminal background gives one category of economically precarious person an advantage. It might not seem that advantageous to the convicted criminal’s new neighbors.

Ultimately, Seattle’s housing market woes stem from decades of exclusionary zoning — making it illegal to build denser housing in most parts of the city. Recent changes to state and local law promise to change that. And as I’ve noted in an earlier post, population growth to our region is slowing, which might give housing supply a chance to catch up with demand. But these trend changes won’t lead to instant relief for rent-burdened families.

Ultimately, tenant protection is a balancing act. Provide tenants with assurance of a safe, decent home and fair treatment without imposing conditions so onerous that landlords decide to cash out. With the city losing tens of thousands of rental units over the past few years, Seattle would appear to be out of balance.