Fixing the Fatal Flaw in the Minimum Wage

It's not that it's too low, or too high. It's that it's hourly.

Several years ago, as an investigator studying the Seattle Minimum Wage ordinance, I was invited to participate in a panel discussion in Portland, Oregon on the topic of minimum wages. The moderator of the panel worked for the Oregon Historical Society, and brought an old book to share. Oregon had been one of the first states to adopt a minimum wage policy in the progressive era, more than a decade before the Fair Labor Standards Act created the Federal minimum during the Great Depression. It was a limited policy, targeting what were then industries where the employees were predominantly unmarried women. For the most part, this was all in the category of trivial knowledge, but there was one aspect of the Oregon minimum wage that stuck out to me.

It was a minimum weekly wage.

Several of the states that experimented with minimum wage policies in the progressive era established weekly standards. And the concept of a weekly minimum entered Congressional debate in the New Deal era. But among the political compromises required to pass the law was an agreement to make the minimum wage hourly.

And that’s problematic. A weekly wage can be set at a level to ensure that the recipient has a decent chance of covering their cost of living — and indeed, Oregon’s weekly minimum was set by a commission that evaluated the cost of living and set the wage accordingly. An hourly wage can’t, unless it’s paired with a regulation specifying a minimum number of hours per week. Which it never has.

An hourly wage creates incentives for business owners and managers to tailor their staffing levels to demand. Is your cafe really only busy for two or three hours each weekday morning? No problem, you can hire employees for just 10-15 hours per week. Does your bookstore really only do significant business on the weekends? No problem, you can hire employees just to work two 8-hour shifts each week.

And this is great for business. It’s fantastic. The only problem is that a significant fraction of the workforce is really looking for more income than what a 15-to-20-hour-a-week job can supply.

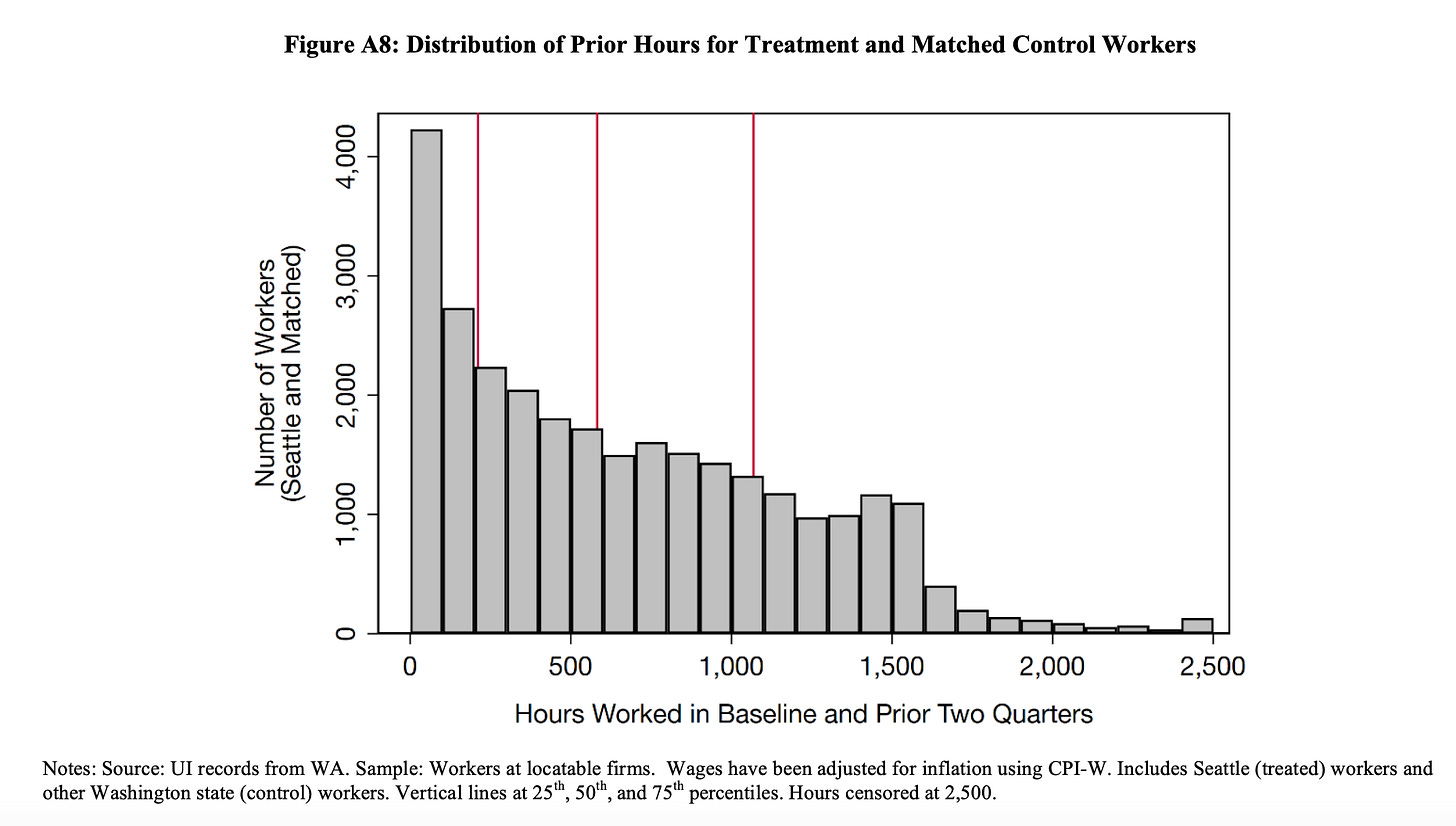

The analysis the Seattle Minimum Wage Study team performed confirmed that the vast majority of low-wage workers in Washington state aren’t getting anywhere close to full-time hours. The figure below is drawn from administrative employment records for Washington state. It tallies up the total number of hours low-wage employees worked over a 9-month period. If the workers had put in reliable full-time effort over this time period, their number of hours should be about 40 (hours per week) times 39 (weeks in 9 months), or 1,560. Hardly any of the thousands of workers in our sample reached that threshold. The typical worker put in closer to 600 hours over nine months, or an average of just over 15 hours a week.

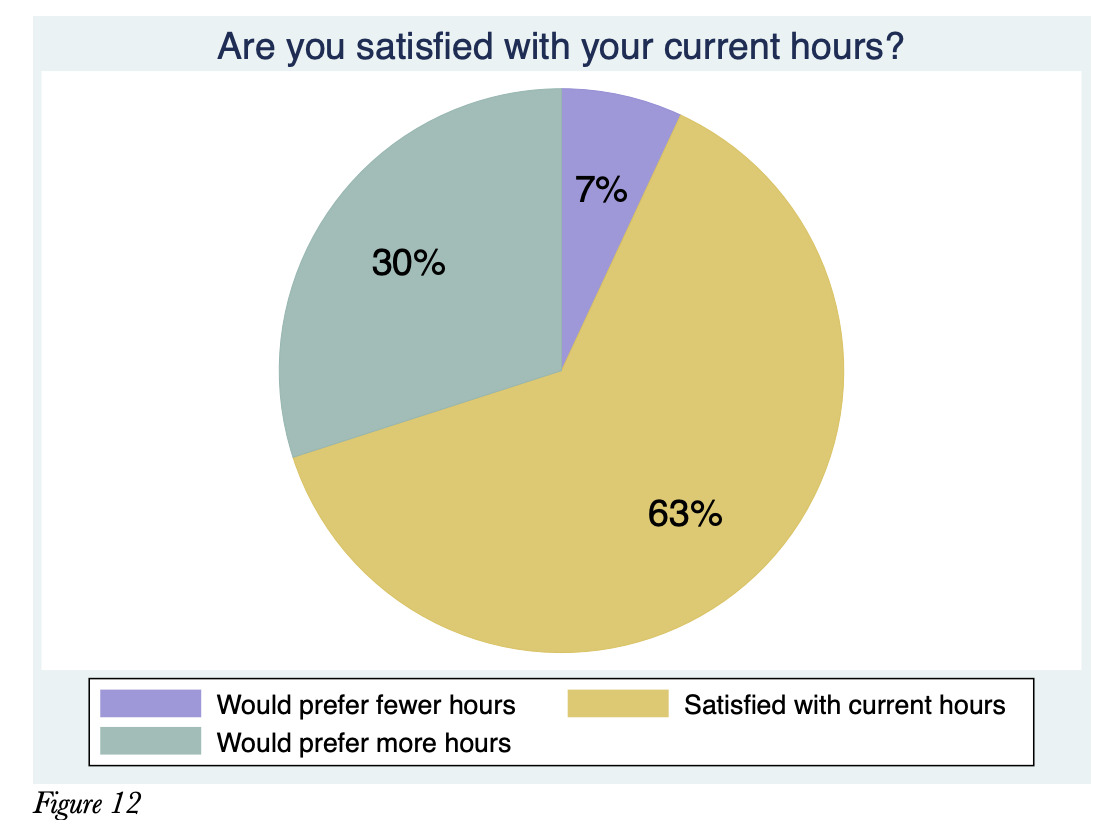

Now one reaction to this image would be to say “well that just shows most low-wage earners don’t really want to work that many hours.” As it happens, at the same time I was working with a team studying Seattle’s minimum wage I was working on another research team preparing a report for the City of Seattle regarding worker scheduling, in the leadup to the city’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance, which took effect in 2017. That work involved a worker survey that asked, among other questions, whether workers were satisfied with the number of hours they received on their current job. And about three in ten responded that they would prefer more hours.

So, to summarize, the predominance of hourly wage setting puts us in a situation where someone trying to support themselves on the basis of work can only succeed if they can get enough hours, and a significant fraction report that they aren’t getting enough.

Seattle’s scheduling ordinance tried to accomplish several things at once. It sought to make schedules more predictable, requiring greater advance notice and disincentivizing last-minute changes to worker schedules. It aimed to ensure workers received adequate rest between shifts. It also hoped to encourage employers to offer more hours to their existing workers before hiring more.

A published evaluation by Kristin Harknett, Danny Schneider, and Veronique Irwin concluded that the scheduling ordinance did improve predictability, and that this in turn improved worker well-being. But there hasn’t been evidence that scheduling ordinances actually lead to workers being given more hours. In the work my team did before Seattle’s ordinance, many employers and employees predicted that the ordinance might lead to fewer hours rather than more — as the penalties against last-minute changes might reduce the likelihood that they could pick up shifts on short notice.

A model minimum wage to address the hours problem

We’ve gotten to the point where the cities and states that made headlines for raising the minimum wage as high as $15 a decade ago are debating going higher still, in large part because of living costs. So let me inject an old idea into this new debate, and suggest that we ought to go back to the original progressive idea of having minimum weekly wages.

The obvious attack on this idea goes back to the notion that as a society we’ve evolved to have many businesses with a small number of “peak” hours per week. Paying a weekly wage to an employee who puts in 5 hours per week at an NFL concession stand doesn’t make sense. So the policy would be tiered in a way that encourages employers to use weekly contracts to the extent possible — by setting the hourly wage at a premium over the weekly wage.

Consider Seattle. At present, the city’s minimum wage is $20.76 per hour. At 40 hours per week that would be $830.40 per week, but of course most low-wage employees don’t get that kind of hours. So imagine a wage-and-hours ordinance that required employers to select a minimum from the following menu:

$830.40 per week for up to 40 hours ($31.14/hour beyond 40).

$25 per hour ($37.50/hour beyond 40).

Noting that the overtime premiums listed in parentheses are the standard 50% in Federal law.

So the deal would be this. Either offer your employees a contract that eliminates their worries about whether they’ll get close to full-time hours, or a contract that pays them a 20% premium per hour. With this structure, the break-even point from the business’s perspective is around 32 hours per week — they’re better off hiring at the weekly wage even if they think the employee will only average 32 hours per week.

If you’re managing that concession stand at Lumen Field, yeah the hourly wage is going to be what works for you. But at the cafe? Or the bookstore? You’ve got an incentive here to try to structure your staffing so that you’re providing a reasonably steady weekly income to as many employees as possible, and just use your hourlies to fill in at the peak. Another way to think about this plan: it’s offering a break on the minimum wage regulation to those businesses that have the capacity or ingenuity to create jobs with more stable, predictable weekly incomes.

There’s no reason you’d have to have just two tiers. Here’s a three-tier example:

$830.40 per week for up to 40 hours ($31.14/hour beyond 40).

$460 per week for up to 20 hours ($25/hour for hours 21-40, $37.50/hour beyond 40).

$25 per hour ($37.50/hour beyond 40).

This provides an intermediate step where business can hire half-time workers at the equivalent of $23/hour, rather than $25, if they can guarantee 20 hours per week. You could sweeten that middle tier still further by adjusting the rates for hours beyond 20. But the structure here gives businesses an incentive to go full-time if they can; by hiring a full-time employee instead of two half-time employees they save about $90/week.

Now, there’s a question of whether $830.40 per week is really enough to get by in the Seattle area. That works out to an average of $3,600/month. If you ask your favorite chatbot to put together a budget for a person living in Seattle on $3,600/month, you’ll see that it can be done but it’s not a very extravagant lifestyle. Studio apartment in an outlying area, relying exclusively on public transit, eating out only once or twice a month. And this is all assuming no dependents. But it’s definitely more feasible on a guaranteed $830.40 per week than on a part-time job with potentially variable hours.

One more thing worth emphasizing: this is a policy specifically tailored to helping adults trying to support themselves. Minimum wage opponents will argue, with basis in evidence, that the structure of this proposal would be particularly damaging to teenage workers looking for their first job. The employers we spoke with a decade ago were reluctant to hire an inexperienced worker at $15/hour, that hesitation would only amplify at $25. But many teens can be available to work full-time hours during the summer; employers would retain the option to let a teen worker go if they prove unreliable or a poor fit for the job. The wage policy could be written to allow employer deductions from pay for missed shifts in a probationary period at the start of employment, or otherwise address the oft-repeated concern that teen workers lose their interest in showing up as soon as their schedule conflicts with their social plans.

But when you get right down to it, the minimum wage addresses a disconnect between what society wants and what businesses want. Society wants people to be able to support themselves through work. That’s at best a secondary concern for businesses, which need to focus on the bottom line. The tiered minimum wage would make providing living-income jobs more compatible with attending to the bottom line.

Overall I'd say Seattle Minimum Wage (one of the highest in the nation) is a success. Figure 12 shows a 63% satisfaction rate. But it would be great more work to help the 30% still looking for more income. Remember when this was still being debated, there was a big chorus singing this would crash Seattle's small business and spike unemployment - Well so far so good, see below.

Here is a perplexity table showing Seattle unemployment faring better than other tech centers and national averages.

Unemployment Rate Table (2021–2025)

Year Seattle San Francisco Boston US National Average

2021 3.3% 5.7% 5.1% 5.3%

2022 2.7% 3.8% 3.7% 3.6%

2023 3.5% 3.9% 3.3% 3.7%

2024 3.7% 4.2% 3.7% 4.0%

2025 3.7% 3.9% 4.4% 4.1%

*Values are rounded annual averages based on monthly data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and regional sources.

I remember the 80's when economists plugged 5% as a healthy unemployment rate. Now I hear 4% is the Feds new number. Seattle is below that, so the big picture looks good, but the marginal workers need more help.

I think the real problem around here is the cost of housing. I suspect the tech boom has priced the lower wage workers out the housing market. I don't think the free market is going to provide a housing solution to the growing income inequality in our region, but maybe someday return to company towns? Who knows, but in the meantime, it wouldn't hurt to issue more manciple bonds for low income housing in designated regions.

Thank-you for following this subject at the local Seattle area. I'm fascinated by your studies. Keep up the good work!